The world changes fast. Once we form perceptions about the way the world is or works, we tend to be a bit too slow to update those perceptions in response to new data.

Last week I posted some analysis of where the scientists who publish in the most selective plant science journals work and live. The short version for those who don’t want to re-read that post:

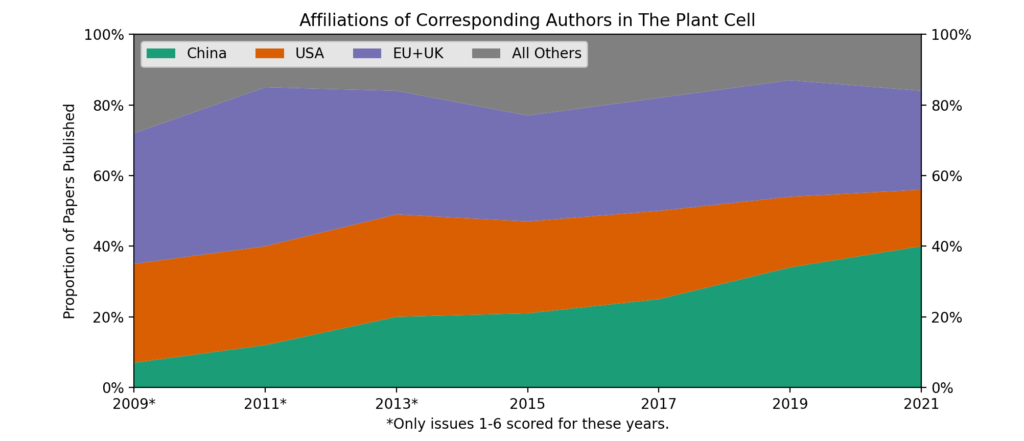

40% of the papers published in The Plant Cell had a corresponding author based in China, 28% from the European Union plus the United Kingdom, 16% from the United States and 16% from the rest of the world (Japan and Korea are particularly well represented in this last category).

I also said that I was really surprised when I actually read through a year’s worth of issues and counted up the numbers. I would have guessed closer to one quarter of the papers came from scientists in the United States and another quarter from China. There are lots of potential reasons to explain why my gut was wrong, but a big one is that just in the length of my scientific career things have changed a lot and my perception is struggling to catch up with the current facts on the ground.

I started graduate school in the fall of 2008. My first full year as a “professional” plant scientist* was 2009. At that time 7% of papers in The Plant Cell were published by authors working in China, 28% by authors working in the USA, 37% by authors working in the EU and 28% by authors working in the rest of the world. In the 12 years since that, China’s share grew to 40%, almost a 6x increase.

So what happened in that 12 year time frame? I don’t have good insight into Chinese policy and funding decisions. But at various points I’ve run into people who have told me that in China, human health research and agricultural research are treated as roughly equal priorities. And China invests a lot in funding plant science, including plenty of dedicated funding for institutes and professors. In the United States plant science is a very small slice of the research our country funds**, and much more of the funding we do have goes out as part of 3-5 year grants for specific projects. Here’s a great visualization of US federal government R&D spending from back when I was a grad student.

Anyway, I’m not sure what the key takeaways are here. I guess 1) It is possible for a country to take big steps forward in scientific discovery and innovation but only if we’re willing to pay for it 2) If you happen to live in the USA, like me, your subconscious may still be assuming that we play a much bigger role in the global plant science research community than we actually do.

The world changes. It is easy to fall behind.

*I was getting paid a bit more than $2,000/month to do plant science. It felt very adult at the time.

**Two big sources of funding for plant science when I started graduate school were the Arabidopsis 2010 project and the Plant Genome Research Program, both run through US National Science Foundation. As you might guess from the name, the Arabidopsis 2010 project ended a decade ago. Plant Genome Research is still around. However, it used to receive dedicated line item funding from congress to conduct research into agriculturally and economically relevant crop plants and the program is now funded at the discretion of the director of NSF.