I use the words basically interchangeably on this site. I know it’s confusing and I at least attempt to pick one and use it all the way through a post (often without success, which I’ll catch, and wince at, days later). The problem is that naturally I use one word or the other depending on context.

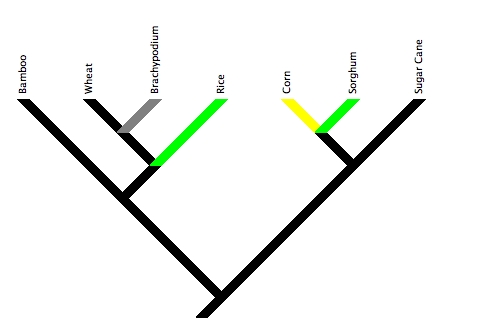

The plant in question is studied internationally and while in America “corn” means those cool looking plants that you see me standing in front of one third of the time when you visit this blog, in british english the same word means any grain. I’ve never heard it explicitly said, but I assume the reason the geneticists who study the plant originally called it maize was to avoid confusion from those mixed definitions. It’s also possible “corn” was still considered a slang term back then, and not the sort of name a well educated scientist should be using regardless.

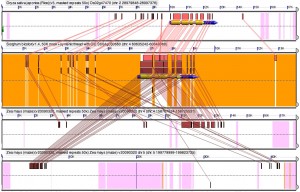

As a result of growing up in the midwest surrounded by corn and getting interested in comparative genomics by way of maize genetics, terms like “corn geneticist” and “corn genome” don’t sound right to my ear and ones like “maize plant” or “maize is selling for $5 a bushel” sound even worse. On the other hand, the sentence “Sequencing the maize genome is going to provide even more powerful tools to corn breeders” sounds fine, but I realize it can be confusing to people whose life experiences are different from my own.*

*An even weirder one: Back when I was still doing science that required writing with pen and paper instead of doing everything on the computer, without thinking about it I’d either cross my sevens or not depending on whether I was writing a number in a scientific context.

Theoretically a crossed 7 is easier to distinguish from a 1, especially on tassel bags and row stakes that are going to be outside, exposed to the elements for months. (And where a mistake has the potential to ruin a year or years of work. It’s not like maize geneticists can run down to Walmart and buy more seeds carrying the genotypes they’ve spent years putting together.)