India has delayed the introduction of their insect resistant eggplants.

Read about it in:

India has delayed the introduction of their insect resistant eggplants.

Read about it in:

An anonymous indian tomato vendor in Chennai, Tamal Nadu. photo mckaysavage, flickr (click to see photo in it's original context)

First, since I didn’t explicitly state it in my previous post, the paper on the longer lasting tomatoes developed by India’s National Institute for Plant Genome Research didn’t report any data on how the RNAi knock-down tomatoes actually taste.* The tomatoes are nearly twice as firm as tomatoes in which these genes are NOT knocked down, so it’s possible they’d seem unpleasantly crunchy, I don’t know how doubling the firmness of a tomato translates into the feeling when a person bites into one.

On the other hand, if the tomatoes do turn out to be tasty and delicious, it’s quite possible the trait could be replicated without genetic engineering. And if that turns out to be true, it’s absolutely the approach anyone developing longer lasting farmers to Indian farmers, or farmers anywhere, should take (for why I’m saying this, check out the bit in bold further into this post). (more…)

Author’s note: This would seem to be the week for vegetables I hated as a kid. Yesterday was onion, today tomato, if there’s a story about brinjal/eggplant in the next few days we’ll have hit all the big ones. 😉

I was recently pointed to an early publication paper that went up on the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences website on Monday, where a research group at India’s National Institute of Plant Genome Research describes two genes from tomato that, when knocked down by RNAi*, result in tomatoes that can remain ripe but not spoiled for up to three times as long as tomatoes where these two genes function normally.

Their approach targets specific genes involved in breaking down certain proteins found in the cell walls of tomatoes (in fact in the cell walls of all plants). Breaking down the cell wall is a key part of ripening in fruits (which the tomato is, botanically if not culinarily). Which makes sense if you’ll think about it for a moment. One of the traits we associate with ripening is getting softer, from bananas to peaches if it’s still crunchy when you bite into it, it wasn’t ripe. What makes plants stiff and crunchy? The strength of their cell walls. Since, unlike vegetables, fruits WANT to be eaten**, as they ripen they begin to break down their cell walls to make themselves more appealing to passing animals. Unfortunately, ripening and spoiling are, in a lot of ways, the same process. If fruits aren’t eaten when they become ripe, they continue to get softer, transitioning from delicious looking -> unappetizing -> inedible -> a puddle of mush on your kitchen counter.

Preventing ripening entirely is relatively easy, and there are plenty of known mutants in tomatoes and other species that never ripen (these naturally mutant tomatoes stay green and hard no matter how long you wait). But getting part of the way to ripeness but stopping before crossing the line into spoiled is a much less tractable problem. (more…)

When I first saw the headline I was hoping I’d find an article describing the first fruits of the turkey genome project (which I talked about back in november.) Instead, and still interestingly, what was just published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences was a study showing that wild turkeys have been domesticated twice by different cultures in the Americas.

The turkeys we eat today come from a breed domesticated by the Aztecs, living in present day Mexico (or proceeding cultures occupying that region). However this study, looking purely at mitochondrial DNA sequences was able to use DNA isolated from bones and turkey droppings to determine that turkeys kept by indigenous farmers in what is now the American southwest represented an independent domestication of wild turkeys from one of a couple of wild turkey subspecies found in North America. Given the uncertainties of archeological dating, the most recent evidence for the existence of this second form of domesticated turkey could be as early as 1400 AD or as late as 1840 AD.

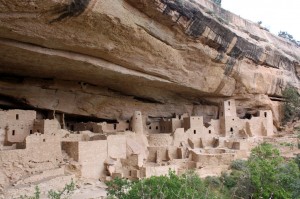

The Cliff Palace, the largest of the ancient villages in Mesa Verde Park. Photo: j-fi, flickr (click to see photo in original context)

What’s fascinating to me is (more…)

Pam Ronald, writing at Tomorrow’s Table points out an interesting interview with Roger Beachy the new head of the National Institute of Food and Agriculture (itself a newly created government organization) in Nature Biotechnology. He talks about everything from restoring support for the, very successful, programs that used to fund the training of plant breeders and plant biologists from around the world* to increasing the number of research grants that have specific money set aside for education and outreach. I’m guessing this is the comment that will get the most play if the interview gets noticed by the popular press:

In the early days of agbiotech, regulations were fairly minimal, which kept development costs low. The safety of a product was judged on the product itself and not the method used to develop it. Regulatory agencies have lost some of that focus in the past ten years. … I am very interested in having a regulatory structure that is science based and gets back to what we originally had.

I continue to be impressed with President Obama’s choice to head up the new agency, as I have been since the appointment of Roger Beachy was first announced. Though I will say I got this part wrong in my original post about Beachy’s appointment:

And on top of that, he’s spent his entire life working in the public and non-profit sectors (places like Cornell, Wash U, the Scripps Institute, and most recently president of the Danforth Plant Science Center). Can you imagine the screaming if Obama had picked someone who’d ever worked in industry to head up the NIFA?

As we’ve seen from the reaction to Roger Beachy’s appointment, finding a respected scientist who has done both basic and applied research, with proven skills as an administrator (plenty of great researchers make horrible administrators) and who’d spent his entire like working in the public and non-profit sectors instead provoked so much screams one might have thought President Obama had appointed Hugh Grant (the CEO of Monsanto, not the actor) to head the NIFA instead of Roger Beachy.

*Such funding contributed to the training of, among others, Gebisa Ejeta, who won the World Food Prize in 2009 for his work developing striga resistant sorghum, and who, from his testimony to the senate foreign relations committee, sounds like he would agree with this goal.

Last week Greg over at Pie-ence was talking about the amazing variety of vegetable crops breed out of a handful of species within the genus Brassica, specifically Brassica rapa and Brassica oleracea.* I’m referring to these as cruciferous vegetables, which is actually a wider category including all the vegetables within the mustard family of plants (scientifically this is called the Brassicaceae). But one of the cool things about having so many kinds of vegetables within the same couple of species is that, because they’re the same species, they can still be interbreed with each other to create “new”** vegetables. (more…)

Check out the article in The Guardian about wheat farming and the future of genetically engineered wheat.

Earlier today I was sent out, through rain and fallen snow, to visit the local grocery store for various last minute cookie ingredients, including confectioner’s sugar. The only brand I could find had this prominent label:

First of all I’ve never understood why people care wether a given cup of sugar come from sugar cane or sugar beets. Regardless of source, white sugar is at least 99.9 percent pure* sucrose. Sucrose is a single molecule with an exact structure that is the same regardless of source. (Like salt crystals, or de-ionized water it’s a pure substance, only one step up from elements like carbon and oxygen).

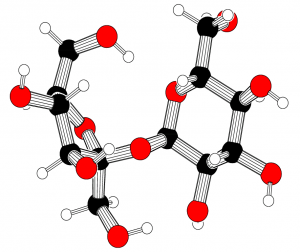

A model of the sucrose molecule. All sucrose, regardless of source, will have this same structure. If it doesn't, it's not sucrose. Image from wikimedia and distributed under the creative commons 3.0 share alike license.

That said, I’ve never before seen a label on a bag of sugar that proudly announced what it is NOT (beet sugar). I don’t know if this is a reaction to the current publicity about herbicide resistant sugar beets, or the old feelings about the, non-existent, differences between sugars refined from different plant sources taken to their logical extreme, but either way, in this christmas of all christmases, is not the time to be kicking beet farmers when they are down. (more…)

Tracked down a paper published just under a year ago in Food Policy (a peer reviewed journal). “The impact of agricultural research on productivity and poverty in sub-Saharan Africa” by Arega Alene and Ousmane Coulibaly.*

CGIAR spending on research targeted at agriculture in Sub-Saharan Africa (178 million dollars a year in 2003) provides 1.3 million people with an escape from extreme poverty (living one dollar a day or less) every year. Simple division would indicate the agricultural research of the CGIAR centers is saving human beings from the trap of extreme poverty at a cost of just under 137 dollars per person. Of course it isn’t that simple, there are both economies of scale** and, eventually, diminishing margins of return*** to consider, but it seems the work of the CGIAR centers in Africa are big enough to have achieved those economies of scale, and, given their calculations on the elasticity on poverty to investment in agriculture, Africa is a LONG way from having to worry about diminishing marginal returns on agricultural investment.

Given the elasticity of poverty reduction to agricultural research spending they calculate (-.22) the marginal cost* of reducing poverty by another person in Sub-Saharan Africa through investments in agricultural research is only $71. (i.e. spending one billion dollars more on agricultural research would save an additional 14 million people from poverty.) This doesn’t consider the additional postive effects of improving local agriculture (for example reducing the incidence of famine).

Finally consider this quote from the paper for a sense of the work the CGIAR centers are funding and try not to feel as impressed as I do: (more…)

Powered by WordPress