The rice of my childhood was brown rice, incompletely stripped of its outer coating to retain more vitamins and minerals. Frankly it wasn’t very appetizing, and it was a pleasant surprise to discover rice can actually be delicious when it’s not also trying to be a health food. Never the less I consider myself to be a relatively unsophisticated rice-eater. If my rice is a different color I’ll probably notice, but a lot of the more subtle variations between different breeds slip by without grabbing my attention.

(transition). I’m going to tell a story of three kinds of rice. But before I do, let me clear something up. The stuff you can buy at a grocery store called “wild rice” (Zizania sp.) is neither wild nor rice*. That’s not a knock against the species, which has quite an interesting history of its own, just the lack of creativity the english language often displays in coming up with the common language names for plant species. (Consider than an alternative common language name for wild rice is “water oats”).

But back to not-wild rice.

Domesticated rice, Oryza sativa, can be divided into two subspecies, indica and japonica. Indica rice breeds tends to have longer grains and be less sticky, while japonica rice grains are shorter and stickier. Attempts to mate the two subspecies produce hybrid plants that had a lot of trouble reproducing.

The earliest evidence for the domestication of rice is found in China and dates back 10,000 years (give or take a few thousand), but it’s estimated indica and japonica rice split from each other 200,000 years ago. The disparity is explained as either two independent domestications of rice from wild species of rice, or (according to at least one paper I have read) that domesticated japonica rice grown in India crossed with the many local rice species native to that region picking up so much new genetic diversity it now appears to be a separate subspecies in both appearance and genetics. Much of the published work on early rice domestication is, for obvious reasons, published in mandarin. If you’re interest in the subject and don’t speak mandarin, here’s a site with a bunch of translated papers.

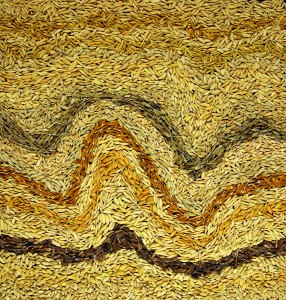

The seeds of twenty cultivars of rice. Photo from the International Rice Research Institute. Click to see more detailed credits for the photo on Flickr.

Regardless of the true origins of the two subspecies of rice, we do know rice was domesticated at least twice in human history. The second domesticated species, Oryza glaberrima was domesticated by farmers three thousand years ago in western sub-saharan Africa (think the general vicinity of Nigeria). True to what you’d expect of a species that was still growing wild when Asian rice was already far down the path to the domesticated form we know today, Oryza glaberrima still has more in common with its wild ancestors which mixed results. It’s harder to harvest and less fun to eat, but better suited to surviving whatever the natural world cares to throw at it.

Why do I care so much about rice? Aside from the fact that it’s the single species responsible for feeding the most people on earth today, rice (the japonica subspecies of Oryza sativa) was the first grass species to be sequenced, and in my work this morning I generated some really weird looking data that turns out to be the result of rice’s genome being more complete/mature/well-studied than the new grass genomes published in the last three years.

There’s another interesting story about the domestication of rice that I’d like to tell, but I’ve learned the hard way not to promise specific posts in the future until I have them written out.

*True “wild rice” is in the same tribe of grasses as real rice, but sorghum is in the same tribe of grasses as corn, but I’m afraid will still look at you very oddly if you start calling sorghum “wild corn”.

**No one wants a banana full of seeds.

I used to work with the rice business and having lived in the Mississippi Delta, I used to pass fields everyday. In February, I had the chance to go to the International Rice Research Institute while in the Philippines on vacation (yes, that is incredibly geeky and I admit it). I learned so much about rice and immediately recognized the photo above as I have a fabric print I got at IRRI. I blogged about it a bit too, of course I was really interested in the communications team too.

Comment by janice — July 31, 2010 @ 10:14 pm

Cool! The IRRI is definitely on my list of places to visit if I ever have a justification to visit the Philippines.

Comment by James — August 2, 2010 @ 10:16 am

I hate common names like ‘wild rice’ that reference other species, especially when they’re not even related, and especially when they lead to ambiguity. That drives me bonkers with the fruits. There’s like a dozen variants on apple (sugar apple, black apple, rose apple, apple pear, ect). My favorite lack of creativity is the native cherry…not only not a cherry, it’s not even an actual fruit.

Comment by Party Cactus — August 4, 2010 @ 12:19 am

It certainly does point to a distinct lack of imagination among the people who first named the species. Although I suppose the more charitable argument is the confusing names reflect a homesickness for foods they’d left behind.

Comment by James — August 4, 2010 @ 1:35 pm