Belated I know. The first section I ever taught could have gone better. Twenty-nine people showed up for a section with an enrolment cap of 25 in a classroom with only 17 desks and no eraser for the chalk board. So that was fun. Still, I made it through a review the parts of a plant (roots, shoots, and leaves), the parts of a flower (sepals, petals, stamens and carpels), and a diagram of why a plant needs both mitochondria and chloroplasts (chloroplasts harvest and store light energy, mitochondria turn stored energy into the form used by the cell, ATP). And the second section I taught, later that same afternoon, went a lot better (In addition to being more sure of the material, I had time to steal back enough desks to bring the room to its rated capacity of 25, hunt down an elusive chalk board eraser, and draw the first set of figures on the board before the students showed up.)

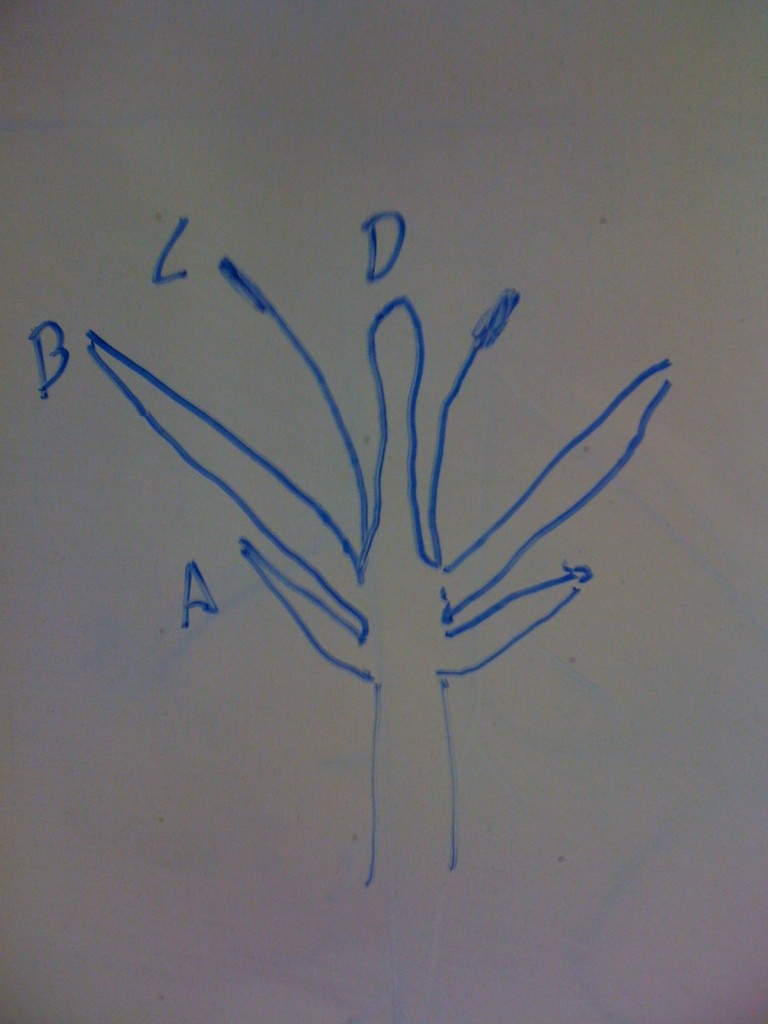

A recreated example (should be familiar to anyone who, like me, took the first two weeks of intro botany):

The basic diagram of four parts of a (eudicot) flower. From the outside in. A: Sepals, small, generally boring green bits that look a fair bit like tiny petals. B. Petals. C. Anthers. The male part of the flower, responsible for producing pollen. D. Carpal(s) The female part of the flower. Pollen lands on the top surface, then grows a tube down into the flower to fertilize the eggs and central cells.

I’ve seen variants of this figure in 3 courses I took as an undergraduate, and now I’m using it myself. I’d be interested to hear if anyone has seen (or can think up) variants that might be easier for people with no background studying plants to grasp.

I can remember what finally got me excited about learning the parts of the flower, but it isn’t any help in trying to get these students excited about plants. I got hooked when I first learned about the ABC model of floral development, and how breaking different genes can, for example: transform the sepals into carpals and the petals into anthers (class A), turn the petals into sepals and the anthers into carpals (class B genes) or create flowers than never produce reproductive organs just some sepals and then lots and lots of petals (class C genes). The story of the ABC model, which I should really write up sometime ::adding it to my long list::, is a discrete and engaging story of how science works, but I don’t have enough freedom in the order I’m teaching material to devote the time to telling that story when I’m supposed to be just teaching parts of the flower. And even if I had the time, throwing gene names and mutant phenotypes at people who probably haven’t taken any biology since high school seems more likely to scare students off then get them hooked on plant biology.

There are a few variations on that theme but really nothing vastly different, at least that i can think of.

The cool thing, to me at least, is that knowing the different floral organs is an essential step to being able to ID plants with confidence. It even makes picking out families of plants alot easier.

Comment by Greg — January 27, 2010 @ 5:20 pm

That’s a good point Greg. I work so much with a few species I forget how many people are interested in being able to identify plants they see in the wild (or at least in the gardens they walk by around town). I’ll have to hit up the other grad student teaching the course, who took the whole 15 weeks of intro botany in for some interesting IDs that can be made from floral formulas.

Comment by James — January 27, 2010 @ 9:00 pm

Hmm… If you could get your hands on single and double roses or something and bring them into class, it might catch some people’s attention. You wouldn’t, I don’t think, have to go into the ABC genes specifically to explain that to get modern roses some of whirl C got been converted into whirl B. Actual, physical plants are always more fun than drawings on the chalkboard anyway.

Comment by Joseph Tychonievich — January 28, 2010 @ 8:14 am

Physical plants really are a lot more fun. It sounds like roses would make a great example if I can track down some of the old fashioned kind. Thanks!

Comment by James — January 28, 2010 @ 10:09 am