There was a recent paper in Science about the mapping of the Artemisia annua genome. I’ve seen several people interpret this as another genome sequence. It’s hard to blame anyone for this confusion given headlines like “Scientists map the maize genome!” to describe the sequencing of the maize genome. So what’s the difference between a sequenced genome and a mapped genome? I’m glad you asked!

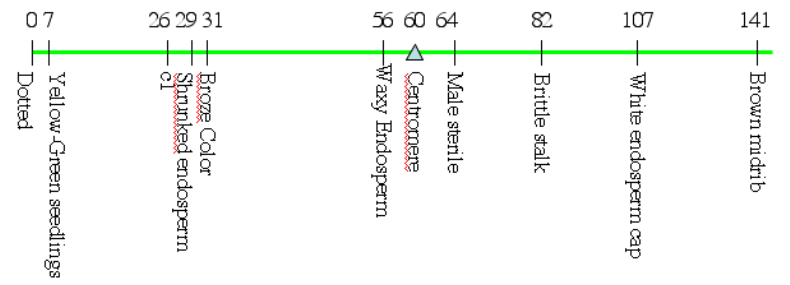

A genetic map describes the order of markers along the chromosomes of a genome. In the oldest maps, these markers would be whole genes. Because genes that are closer together are more likely to be inherited together** by looking at the patterns of inheritance one can figure out the genetic distance between different genes.*** For example (genetic map of maize). Modern genetic maps use smaller markers, often changes in a single nucleotide (say an A turning into T or a C turning into a G) called a single nucleotide polymorphism (or SNP) between different individuals of the same species, but the principle is the same. It’s a map of the order landmarks on a chromosome along with some kind of information that can be used to tell them apart (differences in the DNA sequence itself or differences in the plants, animals, or people that carry different version of the gene).

A genome on the other hand, is the DNA sequence of each chromosome (although usually with the occasional gap). For example:

gggcactttttcgcgtttgcaagttcatggacctaagtggcacaggcgg

acaagttcaggggtcattttttcgggtttgcaagttcatggaccaaagtg

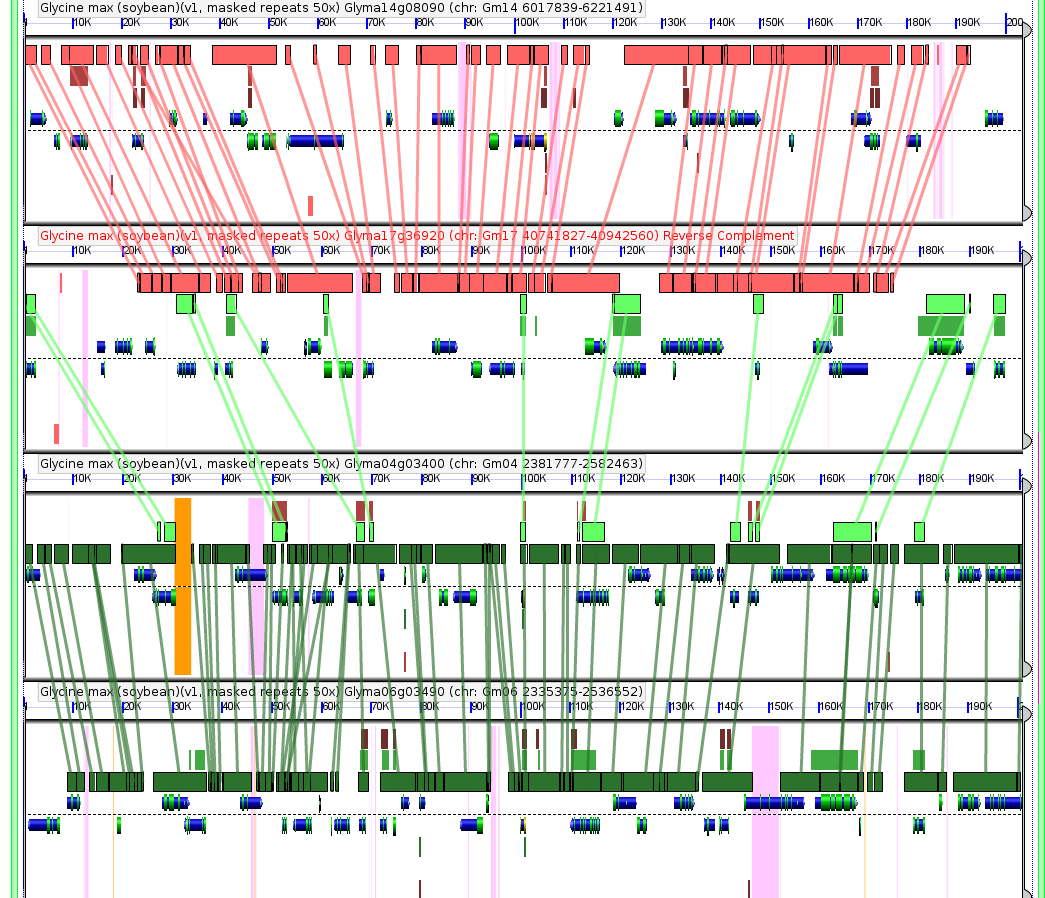

a 100 base pair segment from Sorghum bicolor chromosome 1. Of course sorghums chromosome 1 alone is more than 700,000 times as long, but to the human eye, one piece of raw sequence looks a lot like another. That’s why a genome sequence should also include data which describes which parts of the sequence actually code for genes and which parts don’t. And the end result is the data needed for a tool like CoGe to do this sort of analysis.

Yes I know I’m re-using images, but I’m just fascinated with the soybean genome this month. This compares similar sequences in four regions of the soybean genome. Notice the gene models drawn in green and blue. They were just as much a part of the soybean genome published last week as the raw sequence itself, and allow us to make much more sense out of that raw sequence. Play with this data yourself at: http://tinyurl.com/ydh95oh

For basic science today, a genome sequence is generally more useful than a genetic map. That hasn’t always been true. Barbara McClintock published a map of the order of three genes and the fact they were genetically linked to a physically observable feature on one of the maize chromosomes back in 1931****, more than twenty years before the structure of DNA was discovered. Even today, from a breeding or crop improvement perspective, a genetic map is probably more important than an actual sequenced genome, especially from a cost/benefit perspective.*****

So there’s my best attempt to explain the differences between a genetic map and a genome. But let me leave you with one final metaphor. Imagine a genetic map as the default view in google maps. It tells you were various things are located and how to get from point A to point B. A genome sequence is like clicking the “Satellite View” button. It tells you not just where things are, but what they look like, but costs a lot more to obtain (salaries of cartagraphers vs developing a space program and sending satellites into orbit). Similarly, maps can be used to help piece satellite photos together into coverage of whole countries, and satellite photos can error check and improve the accuracy of maps.

Edit: For more on constructing genetic maps, see this more recent update.

*Artemisia annua is a kind of wormwood. Another species in the genus Artemisia absinthium provided the flavoring for absinthe, but annua‘s claim to fame is that it produces artemisinin, a crucial ingredient in next generation anti-malarial drugs that is in very short supply given annua‘s poor characteristics as a crop. A genetic map of the species holds promise for breeding new varieties that would increase production (and hopefully reduce the costs) of these life saving drugs. I’ve also got to mention that Jay Keasling, a synthetic biologist at JBEI and associated with Berkeley has engineered E. coli to produce artemisinin, with the goal of producing it much more cheaply in bioreactors than it can be harvested from plants grown in the field. It’ll be interesting to see how these two approaches play out.

**It has to do with the way the two copies of each chromosome, one inherited from each parent, are mixed together before they get passed down another generation.

***Genetic distance is measured in centi-morgans which correspond to the chances that genes won’t be inherited together. Let me put that another way. Two genes 1 centimorgan apart will be inherited 99% of the time. Two genes 25 centimorgans apart will be inherited together 75% of the time. This only hold true up to 50 centimorgans where genes are inherited together 50% of the time (this is the same as random chance or two genes on separate chromosomes) so the only way to connect genes farther than 50 centimorgans apart with mapping is to join them together based on mapping how far each gene is from to some gene in the middle. Connect enough genes together and you’ve mapped a whole chromosome. But the biggest thing to keep in mind is that centimorgans aren’t convertible into actual lengths of DNA sequence both because different species mix their chromosomes different amounts, and because different parts of a chromosome are more likely to mix (called recombining) than others. A genetic map and a genome sequence will agree on the order of genes, but not the distances between them.

****McClintock, Barbara The order of the genes C, Sh, and Wx in Zea mays with reference to a cytologically known point in the chromosome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 15 August 1931

*****Having a sequenced genome can really speed up marker discovery for building genetic maps, and genetic maps are often created during genome assembly as a way to bridge together DNA sequences separated by unsequenced gaps, so investing in either one will make it easier to eventually have both.

Barbara McClintock was a badass. I wonder what she could have accomplished had women been respected as scientists at the time.

Comment by mr_subjunctive — January 19, 2010 @ 7:51 am

She sure was! I think part of what made Barbara McClintock so successful was that her personality and research style in some ways minimized the impact of the general lack of respect for female scientists at the time. (And from the stories by PI tells, she was clearly respected in the maize community and at our annual research meeting, at least later in life.) So I’m not sure how much more she would have accomplished if she’d worked in an era with more modern views.

The way I see it, the real question is how much breakthrough research did we missed out on from other women who had scientific potential on the order of McClintock, but weren’t as much of loners and so were more vulnerable to the perceptions of those around them.

(The counter argument of course would be that Barbara McClintock wasn’t a loner by inclination, at least a first, but rather was forced into that role by being an awesome female scientist at a time when many people didn’t believe such a person could exist.)

Comment by James — January 19, 2010 @ 3:16 pm