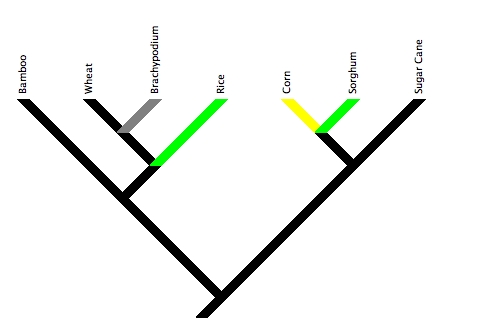

This family tree shows the relationship of a few of the species in the grass family tree that I think people might be most familiar with. Genomes that were published before today are marked in green (there were only two, sorghum and rice), the maize genome which was just published today is marked in yellow, and brachypodium (which you shouldn’t feel at ALL bad if you haven’t heard of) is marked in grey as its genome project is in the final stages (a draft assembly was released to the public last winter) so it’ll probably be the next grass genome to be published. After that I’m less sure, I know there’s a foxtail millet genome project, but I don’t have any idea how far along the process of genome sequencing, assembly and annotation the genome project is.

What’s important to know about the relationship of the sequenced grasses? Well rice was the first grass to be sequenced (as the one of the big three grains, rice, wheat, and corn with the smallest genome), and only the second plant genome ever.

The fact that rice had been sequenced almost certainly influenced the choice to sequence the sorghum genome. Notice how to connect rice and sorghum you have to go through the split at the base of the tree? The lineages leading to those two species split soon after the most recent common ancestor of all grasses alive today, so by comparing them, we can learn more about what the genome of that ancestral grass was like.

The other reason sorghum was such a good choice (besides being a very important crop in its own right; remember it was breeding sorghum for which Gebisa Ejeta won the world food prize this year), is its close relationship with maize (corn). The genome of corn was bound to be sequenced sooner or later (of the remain members of the big three, corn may be big and complex, but sequencing the wheat genome is going to be even more complicated) and sorghum ideally positioned for anyone who wants to study the details of the maize whole genome duplication. Maize’s genome duplication has been dated to approximately 10 million years ago, and sorghum and maize diverged ~11 million years ago*, that’s as close to perfect as anyone could reasonable expect to find, especially for a species that’s a major food crop in its own right.

Other random cool fact: many of the species on the left hand right hand side of the tree (including all three I’ve listed) used C4 photosynthesis. It’s the preference one of the enzymes in C4 photosynthesis for different isotopes of carbon that is the basis of those tests that claim to identify how much of a person’s diet comes from corn. So any sorghum, or cane sugar you eat will count as corn as far as that analysis is concerned.

*To compare that to human evolution, if humans were corn, sorghum would be more closely related to us than orangutans are but less closely than gorillas.