Crops like tomatoes, even heirloom tomatoes, aren’t found in the wild. Domestication of crops usually involves only a relative handful of individual plants. Narrowing the species down to a few hundred (or possibly even a few dozen plants) means only a limited number of copies of each gene will be carried through and many of the variant copies of the genes present in the wild population won’t be included in that number. Keeping the population small for multiple generation reduces variability even more as by chance some rare version of genes in one generation won’t be passed to any of the offspring in the next.

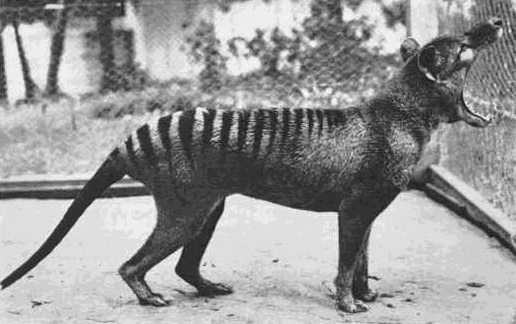

Genetic bottlenecks happen in the animal world as well. Skin grafts between unrelated Cheetahs aren’t rejected because the animals are so genetically similar their immune system can’t distinguish the grafted skin as being different from its own skin. Even less fortunate are the tasmanian devils who have so little genetic diversity that they are being decimated by a transmissible cancer. After fighting with an infected devil, which has tumors on its face and neck, tiny bits of the cancer will get into an uninfected devil’s wounds, and since the immune system can’t distinguish the foreign cancer cells from the devil’s own cells, the cancer cells reproduce unchecked, the trait that makes normal cancers, produced by mutated versions of our own cells, so deadly. And the solution mentioned in the article, to save the species by protecting 200 individuals, while better than letting them all die, will sacrifice even more genetic variability by subjecting the already inbred devils to a new population (and genetic) bottleneck.

I’ve gone off-topic with cool biology.* most crops capture only a small slice of the genetic diversity present in their wild progenitors. Crops can even go through extra bottlenecks, as when a few potatoes, carried back from the new world, gave rise to most of the potatoes grown throughout Europe. Even less diversity, which would have given any plant breeders of the say even less to work with if they tried to develop a blight resistant potato.

To overcome those limitations, today breeders of many crops will hunt down the wild ancestors of that crop and do crosses to bring more of the wild species’ genetic diversity and look for valuable genetic variants that were lost during the original domestication hundreds or thousands of years ago, or new genetic variants that have emerged in the wild since.

It is these intentional introgressions of wild genetic material that make modern tomato breeds more genetically diverse than older tomato breeds such as heirlooms that drew from the more limited range of genetic variants available in tomatoes at the time of their initial breeding. h/t to TheScientistGardener for bringing that awesome fact to light.

*Come on, a disease that spreads when broken off pieces of external tumors get into open wounds is pretty cool, especially when you consider fighting in a crucial part of tasmania devils mating rituals. I do hope the devils can be saved though, Australia has lost enough cool species without the Tasmanian Devils going the way of the Tasmanian Tiger.

Hidy. Off-topic, but: in a comment thread at Garden Rant, I was directed to read the books Genetic Roulette and Seeds of Deception, by Jeffery M. Smith. I found his website, which looks a little shifty, but . . . well, I was sort of wondering if you were aware of any sites rebutting the (fairly lurid-sounding) claims in the books, or even any reviews of the books, positive or negative, from people who are competent to talk about the science involved.

Comment by mr_subjunctive — November 1, 2009 @ 7:50 pm

I’m sorry, looking into the subject it seems there’s a definite need for a well informed rebuttal but I don’t know of one. I’ll ask around see if anyone else does, but until then all I can do is recommend Mendel in the Kitchen and Tomorrow’s Table.

Mendel in the Kitchen is probably better about explaining the history and science of genetic engineering. Tomorrow’s Table is great because it’s written by a husband and wife team who are an organic farmer and a plant geneticist respectively and emphasizes the potential for the organic movement’s goals to be reached using genetic engineering. Both address a lot of the standard criticisms I imagine he makes.

Beyond that if his site or book are making specific outrageous claims let me know and I’d be happy to try and give you one scientist’s perspective. It might even make sense for me to do a more complete review if I can’t find anyone else who has.

Comment by James — November 1, 2009 @ 8:12 pm

It’s not so much any specific thing he says (the site is actually pretty light on claiming anything; presumably one is supposed to buy the books, if you want to know what they say) as the tone. Just on the first page, we have “shocking,” “health and environmental catastrophes,” “dangers,” “threaten,” “chilling,” “controversial,” “toxic,” “misleading,” “corruption,” “profoundly threatens,” “secret,” “victims,” “hidden dangers,” “malignant,” etc. etc. etc.

It doesn’t sound like something one should take seriously. But I would like to know the gist of what he’s saying before dismissing it based on the tone. (If I’d uncovered evidence that GMOs were the Worst Thing Ever, I might sound a little unhinged myself — that wouldn’t make me wrong, necessarily.)

Comment by mr_subjunctive — November 1, 2009 @ 8:44 pm

That’s a tough one. All I can say is if I myself discovered GMOs were the Worst Thing Ever, I’d want the evidence that convinced me front and center.

In the evidence I’ve seen put forward against GMOs mostly falls into two categories:

The first is misinterpreted scientific studies, work that hasn’t been peer reviewed, and stuff that’s barely significant at .05 p-values, which one in twenty studies will be by chance alone (more when they measure multiple criteria like they usually do in feeding studies).

The second is criticisms of the existence of big agriculture companies, gene patents, the idea that farmers can’t save seeds anymore, that it encourages focusing on a few major crops or it gets farmers hooked on expensive new chemicals, those sort of ideas.

A few of those I can be more sympathetic too (others are still based on false assumptions), but they’re not really criticisms of the technology itself, but of the current regulatory and intellectual property environment which is a LONG way from perfect and definitely deserves to be criticized. (Take farmers in India who rarely have the resources to survive even a single bad year, so when the harvest fails, whether it was GM or conventional seed, far too many farmers take their own lives (in all fairness any at all would be far too many.))

Comment by James — November 1, 2009 @ 9:08 pm

A fair amount of the stuff in the second category is stuff I have some fairly grave concerns about myself, though like you say, that’s the sort of thing that is supposed to be in the people’s power to regulate. I think there’s quite a bit of evidence now to support the idea that the people no longer have this power in any real sense, and in that context maybe people should oppose GMO technology because of the potential it has to further empower corporations to . . . y’know, do bad stuff. Stuff that isn’t in the interests of the public. I mean, it’s never just the technology, it’s also the social environment in which the technology is going to be utilized.

This is also making me wonder, as I write this: to what extent are people trying to smear GMO technology with claims it’s unsafe just because they feel like they can’t trust or influence their government? I mean, are people actually believing that the companies are going to sell food that they know will sterilize children, or is this just a way of expressing a general distrust of the government and corporations? Is this a misdirected but valid emotional response to the repeated food scares we’ve been seeing for the last several years?

Probably not really any way to know. But I do believe that when people get weird about a particular issue and are immune to contradictory evidence, it means something. (One of the better examples of this is the 1980s panic over Satanists working in daycare centers — I’ve seen this explained as a societal reaction to an economic situation in which both parents were having to work in order to make ends meet, that the “Satanists” were symbolic of people feeling guilty over abandoning their kids to go to work. I think there’s something similar going on with the antivaccination movement lately, but can’t figure out what.)

Comment by mr_subjunctive — November 1, 2009 @ 9:49 pm

The thing is I don’t think GMOs really DO empower corporations that much more than they already are. Any the main use companies seem to be putting the power they gain to is stifling new competition. As you say, major corporations do have a lot of power in our country, probably a lot more than they should. But if folks who are concerned about that (and I think you’re right, at least some of the anti-GMO sentiment has anti-corporate power at its root), are spending their energy in the fight against GMOs they’re wasting efforts that could be put to much better uses. Health care controls somewhere between a tenth and a seventh of our entire economy. The giant investment banks that created the recession we’re currently suffering through seem to have emerged relatively unscathed and as powerful as ever. Compared to that Monsanto, Pioneer, BASF, Syngenta and Bayer CropScience are all just a drop in the bucket.

My concerns with genetic engineering are things like the current patent and regulatory environment makes it very hard new competition to enter the market. The result is seed prices stay high, and there’s less incentive to improve a more diverse range of crops (although that’s a problem the anti-GMO crowd isn’t guiltless about either). Glyphosate (the active ingredient in round up) coming off patent so farmers who buy round-up ready seeds from Monsanto can buy the herbicide their plants are resistant to from a wider range of sources was a positive step for agriculture as a whole, though I’m guessing it wasn’t good for Monsanto’s bottom line. In not too many years, the earliest GM traits will come off patent too, and that will be even better.

All my concerns come down to: “We’d be getting benefits of the technology if X were different.” Getting rid of the technology gets rid of the problems, but since the problems have to do with potential benefits of the technology we’d come out behind anyway.

Comment by James — November 1, 2009 @ 10:14 pm

“Glyphosate (the active ingredient in round up) coming off patent so farmers who buy round-up ready seeds from Monsanto can buy the herbicide their plants are resistant to from a wider range of sources was a positive step for agriculture as a whole, though I’m guessing it wasn’t good for Monsanto’s bottom line.”

FYI, this was the primary reason that Monsanto laid off ~1,800 employees between June and September (repercussions felt where I work too). I’m sure the alfalfa & sugar beet lawsuits don’t help the bottom line either, but official word was “cheap glyphosate” (from China, presumably).

“the current patent and regulatory environment makes it very hard new competition to enter the market.”

You’ve nailed the problem right here. It takes a $40-100 million investment to get a seed product with confirmed benefits to market (and the costs are always rising). Certainly that’s a fraction of what it costs to get approval for a new pharmaceutical (I think that number is closer to $1B), but it presents the same types of problems for the agricultural industry as well – you’ve got just a few big players with the capital to take a product to market (or absorb the cost if a product fails testing), and those companies buy up or partner with the little idea machines who do the discovery research. And with regulatory costs so high, pharmaceutical companies search for diabetes meds and ag companies make better corn.

What other way can this system work?

Perhaps we need an “Orphan Drug Act” for agriculture.

Comment by Amy — November 2, 2009 @ 2:36 pm

Thanks for the info, Amy. I knew about Monsanto’s layoffs but hadn’t made the connection to glyphosate sales. (They’re cutting their biotech researchers because the chemistry department isn’t bringing in enough money?) Sorry if I came off sounding too glib.

That’s already a huge price tag to get a genetically engineered trait approved, and when you consider how much bigger the drug sector is than agricultural-biotech, it looks even worse for biotech crops. Monsanto is the biggest player in the sector and their total revenue was ~11 billion in 2008, that’s seeds (gmo and otherwise), IP licensing, chemical sales, everything. Pfizer made more than 4x as much, and there are a lot more big drug companies than big plant biotech companies.

Comment by James — November 2, 2009 @ 4:41 pm

Don’t worry about it. Here I go way off topic to your original post:

Monsanto’s layoffs were about 8% of its total workforce, I don’t know how that breaks down among sectors (maybe it was mostly chemical salespeople?) but I imagine some loses occurred in R&D. Monsanto is a publicly traded company, so they have to announce major staff changes to shareholders, but since the company I work for is privately held, I don’t think I can go into much detail about what happened here, but it had an impact.

And every time something bad happens to Monsanto, the bloggers do a little happy dance, but how is 1800 people losing their jobs ever a good thing? there aren’t enough jobs in government and academia to absorb all those people, so they’re not all going to go off and do the noble work. I don’t quite understand the anti-corporatism that seems to be popular right now. Okay, let’s take down the big corporations, but now how do we all stay productive members of society?

You could argue that the corporate model is not the best one. But in an ideal world where research is done solely in academic and government labs, would the end product be that much cheaper? you still have to buy the same materials and hire the same people to do the work. The government would have the same incentive to get a return on investment (or risk going bankrupt) so the cost is recouped either through taxes or by cost of the end product.

The system we have right now isn’t perfect. We still need anti-monopoly and anti-trust legislation. But I’m not convinced that there’s a better model than our current one: high-risk/high-return research (e.g. commodity crops) done with private money and low-risk/low-return research (e.g. papayas, etc) done in public labs.

Comment by Amy — November 2, 2009 @ 7:24 pm

Well a lot of the people doing happy dances probably just want the who area of research shut down and don’t care who is hurt in the process.

The main differences would like that see would be that the technologies used to do the molecular biology needed to develop crops would hopefully be available to all comers (things like error prone PCR and GFP that are now expensive to license) <-- not sure how to manage that one, and the cost of bringing crops to market would be reduced by setting the testing requirements for new transgenes more in line with the risks rather than people's fears. It's my hope that those two changes, lowering the cost of doing research in the first place, and making it less expensive (and less risky) to get genetically engineering foods to market really would both increase the usefulness of the technology and bring more companies into the field (both start-ups and full-sized ones). That way if Monsanto was losing business and laid people off, it would be because some other company was doing it better than they were (and would probably be hiring). But I'm talking about a guess based on a wish and it remains entirely hypothetical unless/until I am picked to be the new King of the World.

Comment by James — November 2, 2009 @ 7:49 pm

“the technologies used to do the molecular biology needed to develop crops would hopefully be available to all comers (things like error prone PCR and GFP that are now expensive to license) <– not sure how to manage that one"

I'm not sure either. This problem is exacerbated by a lack of funding in universities & academic labs, because the incentive is there to control profitable discoveries from campus labs – universities collect IP just like companies do. Is this a new phenomenon? I don't know.

I got really curious about the GFP license – apparently GE owns it. But some academic lab is probably still operating on that IP-transfer money! (and got a bumper with that Nobel Prize $$!)

Hmmm. I think right now, the solution is that the price for freedom to operate with a technology is usually discounted for academic research and more expensive for private ventures (there are technologies that we want to use are are priced out of, even). This is probably the best answer?

I'd love it if universities and their labs were funded well enough that they can offer discoveries freely to everyone (my tax money paid for it, why can't I use it?) but unfortunately I don't see that happening.

I also agree 100% about streamlining the regulation process. I've been really worried lately that this is going to get more expensive as "Big Org" wins more lawsuits against the USDA. 🙁

I hope I'm not unduly distracting you from your NSF (uggggg!).

Comment by Amy — November 2, 2009 @ 9:12 pm

Oops, my spam filter seems to be getting overzealous (sorry I didn’t catch it earlier.)

Comment by James — November 2, 2009 @ 11:36 pm